An Islamic Civilization in Europe: Andalusia – 5

■ Ibrahim Sediyani

– continued from last chapter –

■ WAS TARIQ IBN ZIYAD, THE CONQUEROR OF ANDALUSIA, ACTUALLY A KURDISH, WHICH HAS BEEN DISCUSSED FOR MORE THAN A THOUSAND YEARS AS WHETHER HE WAS AN ARAB OR A BERBER?

If we were to ask, “Who are the two most important figures in Islamic history?”, excluding the Prophet Mohammad and his companions, the pioneer generation we call the “first Quran generation”, I am sure that everyone would unanimously mention the following two names: One is the Kurdish sultan and commander Saladin Ayyubi or with his full name Malikoun-Nassr bavey Mouzaffar Salahaddin Yousouf kurey Najmaddin Ayyubi al-Shadi al-Kurdi (1138 – 93), the conqueror of Jerusalem, the other is the famous commander Tariq ibn Ziyad al- Layti (670 – 720), the conqueror of Andalusia.

Here we will talk about the conqueror of Andalusia, Tariq ibn Ziyad, as per our subject…

Tariq ibn Ziyad is a very important figure for world history, for European history, and for Islamic history. It can even be said that Tariq ibn Ziyad is for the Muslim world what Genoese sailor Cristoforo Colombo (1451 – 1506) is for the Christian world.

There was once a civilization called Andalusia in the Iberian Peninsula in the southwest of Europe, which encompassed all of today’s Spain, Portugal and Andorra, and the southwest of France. This was an Islamic civilization.

The pioneer of this civilization is Tariq bin Ziyad. In 711, the famous Islamic commander Tariq ibn Ziyad landed in Gibraltar with a total of 7,000 mujahideen and defeated the Visigothic King Rodrigo (688 – 712) in Guadelate in the same year. The Visigothic State collapsed and in 712, the arrival of Abu Abdurrahman Musa ibn Nusayr ibn Abdurrahman Zayd al-Bakri al-Lakhmi (640 – 716), the Governor of Ifriqiya, with 18,000 Muslims accelerated the Islamic conquest. In 716, the Muslims conquered all of Spain. (270)

Tariq ibn Ziyad was the commander who initiated the Muslim conquest of Visigothic Hispania (today’s Spain and Portugal) in 711 – 718. He led an army and crossed the Strait of Gibraltar from the coast of North Africa (Maghreb) and united his forces at what is today known as the Rock of Gibraltar.

Today, Gibraltar (Djabal-i Tariq), an autonomous region of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, and the Strait of Gibraltar (Djabal-i Tariq) of the same name are named after him. “Djabal-i Tariq” (جبل طارق) means “Mountain of Tariq” in Arabic. (271)

The Muslims who conquered the Iberian Peninsula in 711 were mostly Berbers and – the official history says that – were led by an Algerian, Tariq ibn Ziyad, under the command of Musa ibn Nusayr, the governor of North Africa of the Umayyad Caliph Hisham ibn Abdulmalik ibn Marwan (691 – 743), whose residence was in Damascus (Dimashk), the capital of today’s Syria. (272) With Tariq ibn Ziyad, for the first time, a general from among the Berbers (or born and raised among the Berbers) who later converted to Islam was commanding an “Islamic conquest” movement. (273)

Tariq ibn Ziyad is a “star” of Islamic history and a “pride monument” of the Muslim world, and at the same time, he is a name that “cannot be shared”. Because there has been a debate in the Islamic world and among Muslim historians for almost a thousand years about “whether Tariq ibn Ziyad was an Arab or a Berber”.

Tariq ibn Ziyad’s name is written as “طارق بن زياد” in the Arabic Alphabet and as “ⵟⴰⵔⵉⵇ ⴱⵏ ⵣⵉⵢⴰⴷ” in the Berber Alphabet.

Since Islamic sources convey everything by “Arabizing” it and Muslim historians are also keen on “making everyone an Arab”, if you read Islamic sources and Arabic works, you will think that Tariq ibn Ziyad was an Arab. Because that is how they tell it. In fact, Islamic sources tell not only Tariq ibn Ziyad and Andalusia, but the entire history of humanity, the history of all religions and civilizations in this way. What is strange and what really surprises me is that no one objects to this situation. However, Tariq ibn Ziyad has nothing to do with Arabism or being Arab.

The Berbers insist that Tariq ibn Ziyad was a Berber, and the vast majority of the world believes the Berbers’ statements on this issue. Therefore, the famous commander Tariq ibn Ziyad is generally accepted as a Berber.

Until I traveled to Andalusia (Ibiza Island) two years ago and did the preliminary work to write this book that you are currently reading, I believed this way. In other words, I knew my whole life that Tariq ibn Ziyad was a Berber, I believed this way.

What if both views are wrong? What if Tariq is neither Arab nor Berber? What if he is neither?

Could such a thing really happen? Could both of them be wrong?

It is clear that the Arabs are wrong and their claims are invalid. Because it is clear that Tariq ibn Ziyad is not an Arab. Besides the Arabs and the sick mentality that accepts every Muslim person as an Arab, there is no one who believes that Tariq ibn Ziyad is an Arab.

But could the belief that he was Berber also be wrong?

If you wish, let’s trace the family roots of Tariq ibn Ziyad, the great man who changed the course of history, and examine what his ethnic affiliation was / could be. Only read what we write from now on if your heart is healthy and be prepared to experience a great shock. Because I will convey information that will surprise you very, very much. And let me also state that the information I will convey is the historical facts that I have reached as a result of months of meticulous work…

Islamic historians are divided on his origin. Some believe that Tariq ibn Ziyad was a North African and Carthaginian Berber who inherited Islam from his ancestors and was the third generation of African Muslims, and that Musa ibn Nusayr was the Emir of Africa. He was released or allied with him. (274)

Medieval Islamic historians provide conflicting data about Tariq ibn Ziyad”s family origins and ethnic affiliation. Some conclusions about his personality and the circumstances of his entry into Andalusia are surrounded by uncertainty. (275) The vast majority of modern sources state that Tariq was the Berber mawla of Musa ibn Nusayr, the Umayyad governor of Ifriqiya. (276)

According to the Berber sociologist Ibn Khaldun or with his full name Waleyeddin abu Zejd Abdurrahman bin Mohammad ibn Khaldun al-Hadrami (1332 – 1406), who is considered the founder of the science of sociology, Tariq ibn Ziyad was from a Berber tribe living in the region known today as Algeria. (277)

However, Ibn Khaldun makes this claim without any information and without providing any source or evidence. In the lower part of the first volume of Ibn Khaldun’s work “Kitab’al-Iber wa Diwan’al-Mubtadā wa’l-Khabar fi Ayyam’il-Arab wa’l- Adjam wa’l-Berber waman Âsharahoum min Zawi’s-Soltan’il-Akbar”, which deals with the origins of the Berbers, there is the following commentary on Tariq ibn Ziyad, without any reference, date or place: “Ulhasa tribe” (Zanata Berber tribe). (278) The only source that Ibn Khaldun relied on when writing this commentary was the book “Al-Bayān’ol-Moghreb fi Ikhtisar-i Akhbar-i Mūlūk’il-Andalus wa’l-Maghreb”, the only work left behind by the Berber historian Ibn Izari or with his full name Abu Abbas Ahmad ibn Muhammad ibn Izari al-Marrakashi (? – 1313), who lived only one generation before him. The book reads as follows: “The name of this leader is Tariq ibn Ziyad ibn Abdullah ibn Ulghu ibn Urfaddjum ibn Nabarghasen ibn Ulhadj ibn It’uest ibn Nafzau; he was Nafzi by origin.” (279)

According to Ibn Izari, Tariq ibn Ziyad was a Berber like himself and most historians share this view because he was a servant of Musa ibn Nusayr, the Governor of North Africa. However, those who hold this view have difficulty in determining the tribe and region where Tariq ibn Ziyad was born and to which he belonged, they fall into contradiction and show differences. (280) Because all of the tribes that Tariq claimed to belong to were not living in Algeria at the time of Tariq ibn Ziyad, but in the Tripoli region in Libya. (281) This clearly shows that the 14th-15th century Islamic historians who claimed that Tariq ibn Ziyad was a Berber and attributed Tariq ibn Ziyad to those tribes without any basis in fact and even by completely fabricating it.

The old historians in the earlier period, such as Egyptian historian, Muhaddis and jurist Ibn Abdulhakam or with his full name Abu’l-Qasem Abdurrahman ibn Abdullah ibn Abdulhakam al-Misri (803 – 71), Kurdish historian, literary scholar and Muhaddis Ibn Athir or with his full name Bavey Hasan Izzeddin Ali kurey Muhammad kurey Muhammad kurey Abdulkarim kurey Abdulwaheed esh- Shejbani al-Djezeri (1160 – 1233), who is considered one of the greatest historians of Islamic history, and Ibn Khaldun did not provide sufficient information about the family origin of Tariq ibn Ziyad. The Algerian historian and biographer Shehabaddin abu Abbas Ahmad ibn Muhammad ibn Ahmad ibn Yahya al-Maqqari al-Tilmisani (1577 – 1632), who lived a few centuries after them and is the author of the encyclopedic work “Nafh’ut-Teb min Ghushn’il-Andalus’ir-Ratib wa Zikru Waziriha Lisan’id-Din Ibn-il-Khatib” on Andalusian culture and civilization, says that Ibn Khaldun mentioned Tariq ibn Ziyad with the epithet “al-Layti”, but this does not appear in modern contemporary editions (editions of his time) of Ibn Khaldun’s works. (282)

The world-famous Kurdish historian, jurist, writer and poet Ibn Khallikan or with his full name Shamsaddin abu Abbas Ahmad ibn Muhammad ibn Ibrahim ibn Abubaker ibn Khallikan al-Barmaki al-Arbili (1211 – 82) wrote that Tariq ibn Ziyad was an Arab from the Sadaf tribes of Hadhramaut (283), and others have also accepted this. Others have suggested that he was probably a freed Arab slave. (284)

Historians have disagreed about the origin of Tariq ibn Ziyad. Some, such as Ibn Izari and the famous Andalusian Berber traveler, geographer and cartographer Abu Abdullah Muhammad ibn Muhammad ibn Abdullah ibn Idris Sharif al-Idrisi (1100 – 66), said that he was a Berber. Others, such as Al-Maqqari and the Syrian Arab writer and poet Khayraddin al-Zyrikli (1893 – 1976), said that he was an Arab. The “Cambridge Encyclopedia of Islam” also claims that he was of Arab origin. (285)

It seems that the 12th century Andalusian Berber historian and geographer Sharif al-Idrisi was the first to say that Tariq ibn Ziyad was a Berber, and referred to him as “Tariq bin Abdullah bin Wamamu al-Idrisi”. (286) Without ever referring to the Zanata Berber tribe and without ever mentioning Tariq’s epithet “ibn Ziyad”, which is known and accepted worldwide today.

As you can see, the claim that the famous commander Tariq ibn Ziyad, the conqueror of Andalusia, was a Berber was first put forward in the 12th century by Sharif al-Idrisi, who was also an Andalusian Berber, and in fact, it has no realistic basis. In particular, the claims that Tariq ibn Ziyad was an Arab are a fabrication and a process of historical distortion that began long after this date. In any case, the claim of being an Arab is a hollow claim that is not accepted in the world. After Berber historians wrote that he was a Berber, Arab historians who “did not want to be left behind” also started writing that he was an Arab. Today, no one in the world (other than Arabs) believes that Tariq ibn Ziyad was an Arab. However, since the vast majority of the world today, and almost all of them, believe that Tariq ibn Ziyad was a Berber (I was of this opinion until last year), the information we have provided above is very, very important and valuable.

So, the claims that Tariq ibn Ziyad was a Berber were first voiced in the 12th century. That is, 400 years after Tariq ibn Ziyad. No one before Sharif al-Idrisi, who was also a Berber, made such a statement and there is no written document regarding this.

May God have mercy on him abundantly; Sharif al-Idrisi is truly a very valuable scholar and his contributions to cartography and geography in particular are invaluable, he has broken new ground in the world. I saw the famous map he drew with my own eyes in the Andalusian Museum on the Spanish Island of Ibiza (Eivissa). But I wish he had only done geography and never tried to be a historian. Despite my great respect and reverence for him, I must frankly state that what he wrote about Tariq ibn Ziyad is literally made up in his own mind because of my devotion to science and truth. And since he made up such a thing at the time, today the whole world believes it as a fact. How sad it is!

Sharif al-Idrisi is not content with just making Tariq ibn Ziyad a Berber. After all, there is no obligation to cite sources, he will not present any documents, whatever he writes will be accepted as true! He goes even further: If you noticed, he does not mention Tariq’s name with the “ibn Ziyad” epithet used and known today, but with the epithet “al-Idrisi”, whatever the connection is. He writes his name as “Tariq al-Idrisi”, not as “Tariq ibn Ziyad”. Would you laugh or cry? In other words, Sharif al-Idrisi not only makes Tariq a Berber, but also cannot stop himself and tries to attribute Tariq to his own family. He tries to make him his relative. Now is this “history”? Is this “knowledge”? Is it “science”?

When Sharif al-Idrisi wrote like this, the Eastern and Western (Muslim and Christian) historians who came after him continued to write like this. Most said Berber, some said Arab. We are sharing some of them with you like this.

Italian historian Paolo Giovio (1483 – 1552) is of the opinion that Tariq ibn Ziyad was an Arab. (287)

The German explorer and scientist Johann Heinrich Barth (1821 – 65), who made discoveries in Africa and was even considered one of the most important European explorers to have discovered Africa, who made scientific preparations before his travels (just like me), who learned African languages and could speak and write Arabic, again using Ibn Khaldun as his source, wrote that Tariq ibn Ziyad was a Berber from the Ulhasa tribe, a tribe indigenous to the Tafne Valley (288), and this tribe currently lives in the Ban-i Saf region of Algeria (289).

Spanish historian and writer Rafael de la Morena (? – ?) says the following about Tariq ibn Ziyad: “This warrior of Berber origin was born in the year 57 of the Hidjri calendar, on November 15, 679 of the Gregorian calendar. He lived in the Rif Mountains of distant Morocco since his childhood, surrounded by nature.” (290)

According to David C. Nicolle (1944 – still alive), a English historian specializing in medieval military history and interested in the Middle East, it is traditionally believed that Tariq ibn Ziyad was born in the Tafneh Valley. (291) He lived there with his wife before ruling Tangier. (292)

Tunisian writer, historian and Islamic scholar Hisham Djait (1935 – 2021) says: “It is known that Tariq was the conqueror of Andalusia. Who is Tariq? He is a Berber mawla from the Nafza tribe, and this tribe is not the Nafza tribe of Tripoli, he most likely settled in the ‘today’s countryside’ around Tangier.” (293)

Spanish writer Josef de Abajo (? – ?) also agrees with him and says: “This brilliant and enthusiastic Muslim warrior showed his skills in martial arts, which allowed this peasant of Berber origin to gain the position of governor of Tangier.” (294)

If we recap the topic, we need to take the following historical facts into consideration one by one:

1 – There is no consensus among historians about Tariq ibn Ziyad’s family origins and ethnic affiliation.

2 – The claims that Tariq ibn Ziyad was Berber were first put forward in the 12th century. That is, 400 years after Tariq ibn Ziyad. The first person to do this was the geographer and cartographer Sharif al-Idrisi, who was also a Berber. Before him and before the 12th century, there is no record, not even a single written document, that says Tariq ibn Ziyad was Berber.

3 – The geographer and cartographer Sharif al-Idrisi, an Andalusian Berber, is not content with just making Tariq ibn Ziyad a Berber, he is trying to attribute Tariq to his own family, to make him his relative. He writes his name as “Tariq al-Idrisi” instead of “Tariq ibn Ziyad”.

4 – Berber historians who tried to make Tariq ibn Ziyad a Berber have also fallen victim to a bit of ignorance. All of the Berber tribes to which they attributed Tariq ibn Ziyad, who was born and lived in Algeria, were living in Libyan territory, not in Algeria, when Tariq was born and lived. This alone shows how the historians who tried to make Tariq a Berber made this claim with a false claim and spoke without any basis in knowledge.

5 – The claims that Tariq ibn Ziyad was Arab are a fabrication and historical distortion process that started even later than this date. After Berber historians wrote that he was Berber, Arab historians who “did not want to be left behind” also started writing that he was Arab.

6 – The reason why almost the entire world believes and thinks that Tariq ibn Ziyad was Berber is the result of the “fabricated history writing” that began in the 12th century, 400 years after Tariq ibn Ziyad.

7 – I am a very good researcher and writer.

So how do we find the truth? How do we correctly determine the family origin and ethnic affiliation of Tariq ibn Ziyad?

This will be a very important effort for us. Because in my opinion, there is nothing on earth more valuable, more honorable and more honest than revealing the truth and adhering to it.

But the problem is: How do we do it? What should we do and what path should we follow?

First of all, as many historians have pointed out, the sources of information on this era and its predecessors are few, and this is a major problem. (295) As Spanish historian and physicist Wenceslao Segura Martínez (1955 – still alive) said, “There is no historical research (documents and archaeology) in the key years at the beginning of the two main Muslim invasions.” (296)

My opinion is that in order to follow this in a healthy way, we need to leave aside the writings of Arab and Berber historians who try to attract this great figure. Because there is no reliability in what those who make Tariq an Arab or Berber without showing any sources or documents write. We also need to leave aside the writings of Italian, German and English historians who are completely outside the subject and the geography of Andalusia, and they are already scanning Islamic sources and repeating what is written there.

The most reliable and perhaps the only reliable way to determine this is to research and find out what the early historical and official records in Spain say. If such official records and historical inscriptions exist, of course. If they do, we need to find and reveal them, and examine what they say about this subject.

This is the healthiest and even the only healthy way. Ultimately, for the Spanish, Tariq ibn Ziyad is a figure on the “other side” and therefore there can be no effort by the official Spanish history or Spanish historians and scholars to distort Tariq ibn Ziyad’s family origins and ethnic affiliation. After all, they are not trying to make Tariq a Spaniard or a Catalan, right?…

Now, hold on tight and read the information we will share with you, our dear readers, if you really have a healthy heart. Because you will encounter information that will shock you:

When I examine official records and historical sources in Spain, I come across very different and interesting information that leaves me in amazement. It is impossible to understand how these have been forgotten and made invisible.

I have a very serious and valuable work on this subject. This Spanish work, called “Colección de Obras Arábigas de Historia y Geografía” (Collection of Arabic Historical and Geographical Works), was published in Spain’s capital Madrid in 1867 by the Royal Academy of History (Real Academia de la Historia) in Madrid.

The 1. volume of this magnificent work, which consists of several volumes, is called “Ajbar Machmúa”. Do not be fooled by the fact that the expression is written according to the rules of the Spanish language, it is actually an Arabic expression. It is pronounced as “Akhbar Madjmoā” (أخبار مجموعة). Its full name is “Akhbar’un-Madjmoātun fi Fath’il-Andalūs”, meaning “Anecdotes on the Conquest of Andalusia”.

The special feature of this exceptional work, now listen carefully, please, is that it tells the history of the Andalusian Islamic Civilization in great detail, from the conquest of Andalusia by Tariq bin Ziyad and the army under his command in 711 to the reign of the Andalusian Ruler Abdurrahman III bin Abdullah al-Marwani (891 – 961) between 929 and 961. It is a Spanish translation of the Arabic work called “Akhbar’un-Madjmoātun fi Fath’il-Andalūs”, whose authorship is unknown, and which is probably the official historical records of the Andalusian Islamic State. (297)

Now, in terms of our subject, that is, for us, could there be a more important source than this?

This treasure-trove of a work written in Arabic, which is the official historical record of the Islamic State of Andalusia and records the entire historical process from Tariq ibn Ziyad’s arrival in the Strait of Gibraltar with ships in 711 to the end of the 10th century, was translated into Spanish by Spanish historian, Arabologist and Arabic linguist Emilio Lafuente Alcántara (1825 – 68). This magnificent work, published in 1867 by the Royal Academy of History (Real Academia de la Historia), the official institution of the Kingdom of Spain, was printed in the printing house called “Estereotipia de M. Rivadeneyra” in Madrid. (298)

The work begins with the Muslim conquest of Spain in 711 and ends with the establishment of the Caliphate of Cordoba. It begins by telling how Musa ibn Nusayr sent Tariq ibn Ziyad to conquer Spain. His attempt to defend the Visigothic King Rodrigo, his love affair with Count Julian (? – ?)’s daughter Florinda la Cava (? – ?), Don Julián (? – 711) and Wittiza (687 – 710)’s betrayal of their children, and Musa ibn Nusayr’s great jealousy towards his commander Tariq ibn Ziyad for his conquests and what he did to eliminate Tariq are all described in great detail.

The common opinion of the scientific world, historians and academics is that this work is generally far from legends and narrates historical events without exaggeration or distortion. (299) For example, Spanish historian Ramón Menéndez Pidal (1869 – 1968) argued that since this work clearly aims for historical accuracy, it should be generally trusted even in the suspicious death of Count Julian’s daughter Florinda la Cava. (300)

Some parts of it date back to the 8th and 9th centuries. An interesting feature of the work is that it does not mention Jews in connection with the conquest of Andalusia. (301)

This work, preserved in only one manuscript, is currently kept in the National Library of France (Bibliothèque Nationale de France) in Paris, the capital of France. (302)

The most shocking information for us in this valuable work, published in 1867 by the Royal Academy of History (Real Academia de la Historia), the official institution of the Kingdom of Spain, is the official history records of the Islamic State of Andalusia, and records the entire historical process from Tariq ibn Ziyad’s arrival in the Strait of Gibraltar by ship in 711 to the end of the 10th century, written in Arabic and translated from Arabic to Spanish by Spanish historian, Arabologist and Arabic linguist Emilio Lafuente Alcántara, is about Tariq ibn Ziyad’s family origin and ethnic affiliation.

From this reliable and “first-hand accurate information” source, we understand that Tariq ibn Ziyad is neither Berber nor Arab. In the very first pages of the work, it is written that Tariq ibn Ziyad was the child of an Iranian family brought from the city of Hamadan in Iran. (303)

In the work, this fact is stated by saying “ilamado Tárik ben Ziyed, persa de Hamadan”. However, we should not understand the expression “persa” here as “Farsi” as it is used in our language, here it means “Iranian”. In many Western languages, the word “Persa” is not used directly in the sense of the tribal name “Fars” but in the sense of “Iran” in the sense of country / geography. For example, the name of our neighboring country Iran is still “Persia” in Spanish and English, “Pérsia” in Portuguese, “Perse” in French, and “Persien” in German. Therefore, “perse” here does not mean Farsi but Iranian. In other words, the work says “Tariq bin Ziyad, an Iranian from Hamadan”. In addition to Persians, there are also Kurds, Azeris, Mazandaris, Baluchs and many other different tribes living in the vast geography we call Iran.

This information shows that they have been teaching us a history full of lies for nearly a thousand years. We took a photo of this work, which shows that we need to rewrite history and is a 100% reliable source, and I am also sharing the photo of the page where this information is given with you, our dear readers, below:

So Tariq ibn Ziyad was neither Berber nor Arab. Everyone already knew that he was not Arab, only Arabs believed in him. But it turns out that the Berber claim that the whole world believed in was not true either. Tariq ibn Ziyad was originally a Iranian from Hamadan.

This treasure trove of a work called “Ajbar Machmúa” is not the only source that sheds light on the history of the Muslim conquest of the Iberian Peninsula. There is also the work “Akhbar Mūlūk al-Andalus” (History of the Andalusian Rulers) by the Iranian Persian historian Ahmad ibn Muhammad al-Razi (887 – 955) (304), the work “Tarikh-i Iftitah’al-Andalus” (History of the Conquest of Andalusia) by the Andalusian Berber historian Ibn Qotiyya or with his full name Muhammad ibn Umar ibn Abdulazez ibn Ibrahim ibn Isa ibn Mozahim al-Ishbili (? – 977) (305), and the work “Al-Moqtabis fi Tarikh Ālimiya’l-Andalus” (Quotes from the Scholars of Andalusia) by the Andalusian Berber historian Ibn Hayyan or with his full name Abu Marwan Hayyan ibn Khalaf ibn Hūseyn ibn Hayyan ibn Muhammad ibn Hayyan al-Andalusi al-Kurtubi (987 – 1076) (306).

Spanish historian Luis Molina Martínez (1940 – still alive), in an article he wrote in the academic journal “Al-Qantara: Revista de Estudios Árabes” (Al-Qantara: Journal of Arab Studies), says the following on the subject: “Given the evidence that the Arab sources give us very different versions of these events, the position to be adopted can never be a democratic position (giving a preferred version according to the number of chronicles that reproduce it) nor a Solomonic position. Distribute the reason equally among the opponents. The occurrence of one version in many sources should not be interpreted with false optimism: We should not therefore believe that we have different, overlapping testimonies that would logically give more credibility to this information; what we have is a single testimony repeated in several works; the evaluation of this testimony should be based solely on the credibility that the origin of the subject under consideration deserves, and not on the success achieved among historians who wrote their works a few centuries after the conquest of Andalusia. The ‘Ajbar’ (the source work “Ajbar Machmúa” we are now discussing – I. S.) is a text consisting of several parts. And it was written at different times.” (307)

In the comprehensive work called “Encyclopædia Universalis”, consists of 28 volumes, 30,000 articles and 32,000 pages and is based in France, which is published by the same organization that publishes the “Encyclopædia Britannica” based in Britain, in the article “Ṭāriq ibn Ziyād” written by French history professor and Arabic language expert Georges Bohas (1946 – still alive), there is information that Tariq ibn Ziyad came from a family of Iranian origin. (308)

According to the earliest sources, Tariq ibn Ziyad was a Iranian born in Hamadan and was a freed slave of Musa ibn Nusayr himself or of the Said tribe. (309) From the Almoravid Period (1090 – 1147) onwards, Berber texts began to record that he belonged to the Nafza tribe. (310)

It is possible that Tariq ibn Ziyad was a freed slave of Musa ibn Nusayr, the Umayyad governor of North Africa (Maghreb). Musa ibn Nusayr instructed him to defend the position of a group of heirs of King Wittiza, who were enemies of the Visigothic Kingdom and held high positions in the Visigothic hierarchy. (311)

Most early Andalusian Arab and Spanish historians seem to agree that Tariq ibn Ziyad was a slave of the emir Musa ibn Nusayr, who gave him his freedom and appointed him as a general in his army. In fact, the world-famous Kurdish historian, jurist, writer and poet Ibn Khallikan refers to him as “Tarik ibn Ziyad”, however, Spanish historians believe that the Kurdish historian Khallikan used the description “Tarik ibn Ziyad” here not in the sense of “Ziyad’s son Tariq” but in the sense of “Tariq who was saved from Ziyad”. (312)

Let me tell you something that might surprise you: The information that there are opinions that Tariq ibn Ziyad came from a family of Iranian origin is also clearly included in the “İslam Ansiklopedisi” (Encyclopedia of Islam) prepared and published by the Turkey Religious Foundation within the Presidency of Religious Affairs, the official religious institution affiliated with the state in Turkey. The following remarkable sentences are included in the article “Târık b. Ziyâd” in the 40th volume of the “Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı İslam Ansikopedisi” (Encyclopedia of Islam of Religious Foundation of Turkey): “There are also views that he originated from Hamadan (Iran) and came from a tribe that migrated to North Africa or that he was of Arab origin. His attribution to the Lays or Sadif tribe is because he was considered a freedman of these tribes. Tariq attracted the attention of Musa ibn Nusayr, the governor of North Africa of the Umayyads, with his talent. After becoming a Muslim, he was freed by Musa ibn Nusayr and provided important services as the commander of the vanguard units in the conquests carried out in North Africa.” (313)

It is really very interesting… From this narration in the “Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı İslam Ansikopedisi” (Encyclopedia of Islam of Religious Foundation of Turkey), we learn that the reason Tariq bin Ziyad used the title “al-Layti” or “al-Laysi” was not because he was a member of this Berber tribe, but because he was a slave freed by this Berber tribe.

This information provided in the “Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı İslam Ansikopedisi” (Encyclopedia of Islam of Religious Foundation of Turkey) is historically 100% accurate. Because this information is also included in many reliable sources that are “original” (i.e. originating from Spain).

A striking statement here is that “After becoming a Muslim, he was freed by Musa ibn Nusayr”. This means that Tariq ibn Ziyad became a Muslim later. In other words, he was not the child of a Muslim family, and in fact, he was not a Muslim himself, but became a Muslim later. He lived as a non-Muslim until a certain period of his life. Even after becoming a Muslim, he continued to be a slave for a while. He was later freed.

This information is also correct, as it is also mentioned in the “Colección de Obras Arábigas de Historia y Geografía”, one of the most reliable sources. Tariq ibn Ziyad was a freed slave after converting to Islam, and in 711, together with another commander, Tarif ibn Malek al-Barghawati al-Maafiri an-Nahai (685 – 760), conducted the first consistent war campaign in the Iberian Peninsula. (314)

So, Tariq ibn Ziyad’s family is a family that was taken as slaves by Arab forces and brought to North Africa after the Islamic armies conquered Iran and Hamadan. Since the capture of Iran by Arab Islamic armies and its “Islamization” was a process that began with the Battle of Qadisiyyah in 636 AD and during the time of 2nd Caliph Omar ibn Khattab (583 – 644) (315), these events are a result of that process. Hamadan was left to the Arab Islamic Caliphate in accordance with the peace treaty signed here after the Battle of Nahavand in 642, six years after the Battle of Qadisiyyah. However, when the people of Hamadan rebelled and expelled the Arabs from the city, it was recaptured by Djarir ibn Abdullah ibn Djabir al-Badjali (633 – 71) in 645, this time through war. (316)

After these tragic events, hundreds of families from Hamadan and other cities in the region were enslaved and concubinated by Arab Islamic forces and taken to the Arabian Peninsula and North Africa. One of these is Tariq ibn Ziyad’s parents and family.

I suggest you pay attention to the chronology: The capture of Hamadan by the Arab Islamic armies in 645. Tariq ibn Ziyad’s birth date is 670. There is only and only 25 years between them. In other words, Tariq ibn Ziyad’s parents were enslaved by Muslim Arabs and brought from Hamadan to Algeria only 25 years later, Tariq was born in Algeria.

Let’s summarize what we have learned so far and the information we have researched and uncovered in general terms:

1 – Although Tariq ibn Ziyad was born in Algeria, who is described as an Algerian Berber in official history today and is believed by everyone in the world to be so, his family was originally from the city of Hamadan in Iran and he was the child of a family brought from Iran to Algeria as slaves.

2 – The claims that Tariq ibn Ziyad was Berber were first put forward in the 12th century. That is, 400 years after Tariq ibn Ziyad. The first person to do this was the geographer and cartographer Sharif al-Idrisi, who was also a Berber. Before him and before the 12th century, there is no record, not even a single written document, that says Tariq ibn Ziyad was Berber.

3 – The geographer and cartographer Sharif al-Idrisi, an Andalusian Berber, is not content with just making Tariq ibn Ziyad a Berber, he is trying to attribute Tariq to his own family, to make him his relative. He writes his name as “Tariq al-Idrisi” instead of “Tariq ibn Ziyad”.

4 – Berber historians who tried to make Tariq ibn Ziyad a Berber have also fallen victim to a bit of ignorance. All of the Berber tribes to which they attributed Tariq ibn Ziyad, who was born and lived in Algeria, were living in Libyan territory, not in Algeria, when Tariq was born and lived. This alone shows how the historians who tried to make Tariq a Berber made this claim with a false claim and spoke without any basis in knowledge.

5 – According to the earliest sources, Tariq ibn Ziyad was a Iranian born in Hamadan and was a freed slave of Musa ibn Nusayr himself or of the Said tribe. From the Almoravid Period onwards, Berber texts began to record that he belonged to the Nafza tribe.

6 – The claims that Tariq ibn Ziyad was Arab are a fabrication and historical distortion process that started even later than this date. After Berber historians wrote that he was Berber, Arab historians who “did not want to be left behind” also started writing that he was Arab.

7 – The reason why almost the entire world believes and thinks that Tariq ibn Ziyad was Berber is the result of the “fabricated history writing” that began in the 12th century, 400 years after Tariq ibn Ziyad. (Let me confess again: I was of this opinion until last year, and I believe the same.)

8 – In the early historical and official records in Spain, it is clearly written that Tariq ibn Ziyad was the child of a family from the city of Hamadan in Iran. This information is available in many reliable sources, especially the treasure trove called “Colección de Obras Arábigas de Historia y Geografía” (Collection of Arabic Historical and Geographical Works), which is the Spanish translation of the Arabic work called “Akhbar’un-Madjmoātun fi Fath’il-Andalūs”, which is the official historical records of the Islamic State of Andalusia and records the entire historical process from the time Tariq ibn Ziyad sailed into the Strait of Gibraltar in 711 to the end of the 10th century. The common opinion of the scientific world, historians and academics is that this work is generally far from legends and narrates historical events without exaggeration or distortion. In the comprehensive work called “Encyclopædia Universalis”, consists of 28 volumes, 30,000 articles and 32,000 pages and is based in France, which is published by the same organization that publishes the “Encyclopædia Britannica” based in Britain, in the article “Ṭāriq ibn Ziyād” written by French history professor and Arabic language expert Georges Bohas, there is information that Tariq ibn Ziyad came from a family of Iranian origin.

9 – The capture of Hamadan by the Arab Islamic armies in 645. Tariq ibn Ziyad’s birth date is 670. There is only and only 25 years between them. In other words, Tariq ibn Ziyad’s parents were enslaved by Muslim Arabs and brought from Hamadan to Algeria only 25 years later, Tariq was born in Algeria.

10 – Tariq ibn Ziyad is not the child of a Muslim family. In fact, he himself was not a Muslim until a certain period of his life. He was probably a Zoroastrian. This person, who was in the status of a slave, later became a Muslim. He was also freed after a while.

11 – The reason why Tariq bin Ziyad used the title “al-Layti” or “al-Laysi” is not because he was actually a member of this Berber tribe, but because he was a slave freed by this Berber tribe. In fact, Spanish historians think that Kurdish historian Khallikan used the expression “Tarik ibn Ziyad” here not in the sense of “Ziyad’s son Tariq” but in the sense of “Tariq who was saved from Ziyad”.

12 – I am a really good researcher and writer.

After identifying these, it was time to uncover Tariq ibn Ziyad’s ethnic affiliation. So how was I going to do this? After all, in the vast geography we call Iran, there are Persians, Kurds, Azeris, Mazandaris, Baluchs and many other different tribes. But what interests us is only Hamadan and we had to identify the demographics of that city at that time.

Now I would like you to read what I will tell you carefully:

After identifying these, I contacted some Iranian Islamic scholars and historian friends. Some of them were still living in Iran, while others were in other countries outside of Iran because they were opponents of the regime. But all of them were scholars. I made a request to them: Since I was busy writing about the main topic, namely the Islamic Civilization of Andalusia, and without mentioning that I intended to reveal the family origin and ethnic affiliation of Tariq ibn Ziyad, saying “for a study I am busy with”, I asked them, to go into the archives of the city of Hamadan for me, scan historical sources and old Persian works related to Hamadan, and inform me of the ethnic distribution of the population of Hamadan in the 7th century, that is, at the time of the “Islamic conquest”.

I said the following to these Iranian scholarly friends of mine, some of whom live in Iran and some outside of Iran:

“Aghadjan! I would like to ask you something, with great importance and gratitude. Please do this for me, because it is very, very important to me. I need this information for a scientific study that I am currently engaged in.

I need the ethnic distribution of the population of the city of Hamadan in the 7th century and before. When the Arab Islamic armies took over, was the population of Hamadan Kurdish, Persian, or something else?

Please determine this for me and let me know. Because this is very important to me right now.

Please, please, will you go into the archives of the Hamadan City Municipality, find old official records, find old Persian works and reveal this, do whatever you can, but I beg you to do this for me.”

I did not stop there. I called my fellow citizens (Kurds and Turks) living in Turkey, who are mainly Iranian experts and researchers and writers, and I asked them to reach old Persian works and reveal them.

And I waited for their answers, not for days but for weeks. Thankfully, they spent their time for me and with a feverish effort, they revealed that the population of the city of Hamadan in the 7th century, that is, at the time of the “Islamic conquest”, was entirely Kurdish.

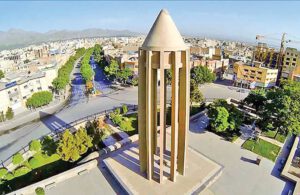

Hamadan, located in the geography of Eastern Kurdistan (Western Iran), is one of the oldest cities in Iran and the world. Located at the foothills of the 3574-meter-high (317) Alvand Mountain, an extension of the Zagros Mountains, the heart of Kurdistan, at an altitude of 1741 meters above sea level, this city is considered one of the coldest cities in Iran.

The name of this city was first encountered in 1100 BC and is mentioned as “Amdane”. It is also known as “Hegmetane”, “Hegmetan”, “Ekbatan”, “Ekbatana”, “Amedane”, “Anadana”. The name of this city is “Amedane” in Neo-Assyrian Aramaic inscriptions. Since the Assyrians called the Medes Kurds “Ameda”, this name must be derived from the word “Med”. This is a settlement founded and built as a city by the Medes, the ancestors of the Kurds. For this reason, even the phrase “med” in the name of the city of Hamadan refers to the Kurdish Medes nation, and the name of the city in its early periods, “Amedane”, literally means “place of the Medes” or “place where the Medes lived”. (318)

As a result of a series of interdisciplinary scientific studies based on paleo-archaeological genetic evidence, especially DNA studies conducted on skeletons, which have been ongoing since 2000 on the scientific origin of the Kurds, it has been determined that the Kurds, who still live in the Hurrian-Mittani lands with their dense population, have the highest percentage of ethno-genetic similarity to these Aryan (R1a1) ancestors. As a result of the DNA sequencing conducted on the Kurdish ethno-genesis, it has been revealed that the Hurrians, Mittanis, Gutians, Lolos, Cardus, Kirtis and Medes are the progenitors that formed the ethno-genesis of the Kurds. (319)

Scholars and historians generally believe that the Medes were a starting point for the Kurdish and Baluch ethnogenesis. (320)

In the “Encyclopedia of the Developing World”, a respected work worldwide, it is clearly stated that most of the civilizations and states in Ancient Mesopotamia were founded by Kurds, that the Hurrians, Kurtis, Gutians, Hittites, Kassites, Mittanis, Adiabenes, Sofhanes and Medes were Kurds, and even when referring to the Hurrian lands, the term “Hurrian Kurdistan” is used. All of these are mentioned in the article titled “Kurds”. (321)

During the time of the Medes, the ancestors of the Kurds, the city of Hamadan was called “Hegmatane”, which means “gathering place” in the old Kurdish language spoken by the Medes (in fact, in today’s Kurdish dialect, which has not undergone much change, it is “Hê-koma-dane” or “Ê koma danîne”). (322) The Greek word “Ekbatan” is also pronounced the same as Hegmetane. (323) Over time, the name of Hegmatane changed first to “Ahmtan”, “Ahamdan”, and then to “Hamedan” during the Sassanid period. (324)

As ancient history studies have revealed, at the beginning of the 2nd millennium BC, events occurred that caused the migration of two nations living in this region’s vast lands. At this time, two Aryan nations, the Medes (Kurds) and the Persians (Farsians), whose languages differed only slightly, moved to the southern lands. The Medes (Kurds) nation was located in the southeastern region of Lake Urmia, between Hamadan and modern Tabriz, and later advanced towards Isfahan. (325)

There are differences of opinion among both the accounts of Greek historians and geographers and Islamic historians about the time of construction of the city of Hamadan, its construction method and the name of its founder. According to the ancient Greek historian Herodotus (484 BC – 425 BC), this city was founded by the first Med King Dayiko (? – 678 BC). (326) (As you can clearly see, the name of the first king of the Medes is Kurdish and means “Mother’s beloved son”.)

In the time of the Medes, the most important caravan routes met at Ekbatana (Hamadan) and this city was considered the heart of the ancient Medes. They generally believe that Hegmetane was a gathering place, a marketplace or something similar. At one of the general meetings of the Tribal Union among the Medes Kurds, Dayiko was elected as the leader (the customs and culture of tribal meetings among the Kurds have not changed at all for thousands of years). Dayiko chose Hegmetane (Hamadan) as the capital. The location of this city was very suitable for the capital, because it overlooked the road to Babylon and Assyria. (327)

Hamadan was founded by the Medes, the ancestors of the Kurds. The ancient Greek historian Herodotus states that Hamadan was the capital of the Medes around 700 BC. According to Herodotus’ writings, the first king of the Medes, Dayiko, ordered the construction of a massive fortification in Ecbatana, consisting of seven fortresses and royal palaces known as the Palace of Hefthasar (the name of the palace is also Kurdish). (328) Most researchers of history and archaeology believe that the Hegmatane Hill and modern structures in the heart of the city of Hamadan are the remains of these facilities. (329)

The Kurdish Civilization of Media played a colorful role in the establishment of the civilization. The Persians owed their use of parchment paper and pens instead of clay tablets for writing and their use of numerous columns in the construction of buildings to the Medes. Most of the moral laws and religions of the Persians were imitated by the Kurdish Medes. In terms of architecture, this was the architecture of the Medes period, which later became the basis for the construction of magnificent buildings such as Persepolis (Takhtey Djamshid). The Persians actually stole the rule of the Medes and destroyed them, then created a story of their own and justified themselves.

The capture of Iran by Arab Islamic armies and its “Islamization” is a process that began with the Battle of Qadisiyyah in 636 AD during the reign of 2nd Caliph Omar ibn Khattab. (330) Hamadan was left to the Arab Islamic Caliphate in accordance with the peace treaty signed here after the Battle of Nahavand in 642, six years after the Battle of Qadisiyyah. However, when the people of Hamadan rebelled and expelled the Arabs from the city, it was recaptured by Djarir ibn Abdullah in 645, this this time through war. (331)

According to the Mazandari historian Tabari or with his full name Abu Djafer Muhammad ibn Djarir ibn Jazid al-Amuli at-Tabari (839 – 923), the gate of Hamadan was first opened to the Muslims in 642 CE (21 AH), and in some other sources it is in 640 CE (19 AH) and shortly after the capture of Nahavand by the Arab Islamic army. After the Arabs took control of Hamadan, the people of Hamadan first accepted the tribute and made peace, but after a while, the ruler of Hamadan, referred to by historians as Haysh (? – 644) and nicknamed Khūsrowshanom, refused to obey the Arabs, and ordered the city to be surrounded by a strong fence that could resist the Arabs. In the year 644 AD (23 AH), 2nd Caliph Omar ibn Khattab assigned a group of soldiers to oppose the Hamadan Revolt. In Deh, known as Rajrud, a bloody battle continued between the two sides for three days and three nights until Khūsrowshanom was killed and the Hamadanites fled, leaderless, and six months later Hamadan was captured a second time by the 3rd Caliph Uthman bin Affan (576 – 656). The Arabs came to power. During the Caliphate of Uthman, the people of Hamadan started a new rebellion and uprising and Uthman assigned Abu Abdullah Mughire ibn Shuba ibn abu Āmir ibn Masoud as-Sakafi (600 – 70) to suppress the rebellion. (332)

After the conquest of Hamadan by the Muslim Arabs, some Arab tribes gradually settled in this city and the Ban-i Salama tribe among them took over the administration of the city. (333)

The Arabs made Hamadan the capital of the province. Hamadan had become so important and prestigious in the eyes of the Muslim Arabs that the Arabs considered the opening of this city after the conquest of Nihavend to be their greatest victory against the Sassanids. (334)

The story of our hero in this book, Tariq ibn Ziyad, begins right here. During the Arab Islamic conquests, dozens of families from Hamadan, whose population was entirely Kurdish, were forcibly taken to the Arabian Peninsula and North Africa by the Arabs as slaves and concubines.

One of these Kurdish families is Tariq ibn Ziyad’s parents and family.

Year, 645.

Tariq ibn Ziyad’s parents, a Zoroastrian Kurdish couple whose names are unknown, were enslaved and taken from Hamadan to Algeria. This family later joined the staff of Musa ibn Nusayr, the Umayyad’s North African Governor, in Algeria, and became his slaves.

Exactly 25 years after this tragic event, that is, only 25 years after his parents were taken from Hamadan to Algeria, Tariq was born.

Year, 670.

Tariq ibn Ziyad, born in Algeria, was born and raised among Berbers, despite being a Kurd, he was raised as a Berber.

His parents were not Muslims, they were Zoroastrians. He was not a Muslim at first, but lived as a Zoroastrian until a certain period of his life. He later became a Muslim and after becoming a Muslim, he was set free by Musa ibn Nusayr.

This is the essence and the root of the matter. This is the mirror of truth.

There are so many interesting things in the sources that one is truly amazed as one researches, reads and learns.

The Berber sociologist Ibn Khaldun, who is considered the founder of the science of sociology, in his book “Tarikh’al-Berber” (History of Berbers), which is the 6th and 7th volumes of his magnificent work “Kitab’al-Iber wa Diwan’al-Mubtadā wa’l-Khabar fi Ayyam’il-Arab wa’l- Adjam wa’l-Berber waman Âsharahoum min Zawi’s-Soltan’il-Akbar”, later published as an independent work, says that there was a large Kurdish population living in Algeria and that they lost their ethnic identity and became “Berbers” over time. (335) Ibn Khaldun even gives the names of some of the Kurdish tribes in this work. (336)

As I said; there are so many interesting things in the sources that when one researches, reads and learns, one is truly astonished. And we painfully understand how they have made up and told us lies for a thousand years, and what kind of lies they have put us to sleep with, whether in schools, mosques, official education or religious education.

For example, what is it that we are told, whether in formal education in schools, in so-called “scientific” education in academia, in religious education in mosques, in so-called “Islamic” education in the field of theology? Tariq ibn Ziyad was the commander of Musa ibn Nusayr, the North African Governor of the Umayyad Empire, whose center was Syria – Damascus. Musa ibn Nusayr assigned Tariq ibn Ziyad to conquer Spain. Tariq ibn Ziyad, upon receiving this assignment, went and conquered those lands in 711, and thus began the Islamic Civilization of Andalusia. This is what we are told, isn’t it? We all “know” this.

Well, could you have ever thought that this was a big lie? Could such a thing have ever occurred to you?

Hold on tight; I am now telling you the things that will really shock you and shake you the most:

It is even debatable whether Tariq ibn Ziyad – as we are told – really set out to conquer Spain on Musa ibn Nusayr’s orders and assignment, or whether Tariq acted on his own, without listening to Musa or obeying his orders, by gathering a few warriors around him, even though Musa ibn Nusayr did not want such an operation and even tried to prevent Tariq. There are debates among different sources on this important issue, and many historians say that Tariq ibn Ziyad acted on his own. According to historians, Tariq ibn Ziyad took on tasks that were never given to him, and let alone conquering Spain upon Musa ibn Nusayr’s orders, did not even inform Musa ibn Nusayr while he was conquering Spain. When he learns about the conquest of Spain, Musa ibn Nusayr becomes very angry and starts to feel a grudge against Tariq ibn Ziyad. Musa ibn Nusayr is thinking of arresting Tariq ibn Ziyad and chaining him up, and even killing him. I am sharing the link to the Spanish academic article that includes this information, which I believe you, our dear readers, are currently reading with astonishment, and where the evaluation is made about it, as a footnote below. The author has provided dozens of scientific sources about these and has collectively stated the sources he used under the article. (337)

What should we understand from all this? The most difficult thing in the world is to tell the truth against one’s “own stupidity” and I think we should be honest, we should tell the truth against “our own stupidity”: There is only one thing we need to understand from all this, and that is that only lies are told to us in both official and religious education by being called “History”.

What? Tariq ibn Ziyad was the commander of Musa ibn Nusayr, the governor of the Umayyads in North Africa, Musa sent Tariq to conquer Spain, when Tariq ibn Ziyad landed on the Iberian Peninsula with ships, Musa ibn Nusayr and the Umayyad sultanate in Damascus rejoiced, they immediately prostrated themselves and performed a prayer of gratitude, and then they danced an oriental dance accompanied by the songs “Shiki Shiki Baba” and “Allah Allah Ya Baba – Sidi Mansur Ya Baba”, this conquest was a great success for the Umayyads… Lie upon lie!

The Kurdish commander Tariq ibn Ziyad, who was a magnificent man, carried out this conquest independently with his own mind and the Berber warriors he gathered around him. He did not even inform Musa ibn Nusayr, in fact when Musa and the Umayyads heard about this they became very angry, they considered arresting Tariq ibn Ziyad and chaining him, and even killing him. In other words, the conquest of Spain in 711, the conquest of Andalusia, was not an achievement of the Umayyads, on the contrary, it was an achievement that was achieved despite the Umayyads.

Oh Tariq ibn Ziyad!… What kind of a person are you? What a magnificent man are you? What kind of a brave human being are you?

Imagine, 66 years ago, before he was even born, his parents were brought from Iran, Hamadan to Algeria as slaves. He was also born 25 years later, 41 years ago, in Algeria as a child of this slave family. He grew up and was raised among the Berbers as a child of a Zoroastrian and enslaved Kurdish family. He became a Muslim in his 30s and was freed. Having just turned 40, he gathers dozens of Berber warriors around him and commands them, and at the age of 41, he conquers the vastness of Spain. He does this despite the Umayyad Caliphate and the North African Governorship of this empire, knowing that he will earn their wrath and that they will punish him.

He is one of the most extraordinary figures in history, in my opinion.

It’s not finished yet, but… I want to continue sharing my posts by researching forgotten historical sources from the early period that not many people know about. Because there are things that one wonders what happens when one learns them.

The first reference to Tariq ibn Ziyad in historical sources, in other words the oldest source mentioning Tariq, is the “Mozarabic Chronicle” written in Latin in 754. Although it was written only 43 years after the conquest of Spain, it interestingly mentions Tariq as “Taric Abuzara”. (338)

The “Mozarabic Chronicle”, also known as the “Chronicles of 754” or the “Chronicles of Spain”, is a Latin historical compilation consisting of 95 chapters. It was written in Andalusia by an anonymous Mozarabic (Christian) chronicler. This chronicle is the first known reference to Europeans as “Latins”, and describes the Europeans as having defeated the Muslims at the Battle of Tours and Poitiers in 732. (339)

It was written in 754 by a Christian cleric living in Andalusia, a region in the Iberian Peninsula where Muslims were the dominant and majority. At that time, Christians living under Muslim rule were called “Mozarabs”; the current name of the chronicle is derived from this term. Modern studies estimate its value as a source for a relatively weak period. It is considered the most reliable narrative source for the last phase of the Visigothic Empire, describing its destruction during the process of Islamic expansion. It is also the oldest source describing the Muslim conquest of the Iberian Peninsula. (340)

The “Mozarabic Chronicle” covers the years 610–754, a period for which there are few contemporary sources to verify its accuracy. It begins with the accession of ‘Irákleios (575 – 641) to the Byzantine throne and is considered an eyewitness account of the Muslim conquest of Hispania. (341)

This work has survived to the present day in three manuscripts, the oldest of which dates back to the 9th century, divided between the “British Library” in London and the “Biblioteca de la Real Academia de la Historia” in Madrid. The other manuscripts date back to the 13th and 14th centuries. (342)

There are really interesting things in the oldest sources. Finally, I will share some “a bit of tabloid” information about Tariq ibn Ziyad this time:

Some sources state that Tariq ibn Ziyad had a woman with him on all his expeditions and that when they crossed to Gibraltar by ship in 711 and conquered Spain, Tariq was accompanied by a woman named Ūmmū Hakim. However, the nature of their relationship remains unclear; whether this woman named Ūmmū Hakim is Tariq ibn Ziyad’s wife, sister or lover is unknown. (343)

This is also strange. Who is Ūmmū Hakim? It is unknown…

I think she is Tariq’s wife, but I still have doubts in my mind. Because during that period, commanders would not take their families, wives, or sisters with them when they went on such expeditions. They would never take them on such a dangerous expedition, such as a “suicide attempt”, with a small army challenging the whole of Europe.

Since the woman’s name is Ūmmū Hakim, it means that this woman is a mother. She has a child named Hakim. If she is Tariq’s wife, then the couple has a child named Hakim. However, if the woman is a widow, then she could be Tariq’s lover.

According to the same sources, this woman was a slave in Algeria. Tariq took she with him (most likely kidnapped she) when he went on expeditions. (344) So it seems like they ran away together. If so, the woman could be of the same ethnic origin as him (Kurd); indeed, Tariq was a slave until a few years before him, then he was freed. The woman could be a slave who has not yet been freed.

It is a very strange situation and a truly mysterious event.

Crazy questions come to my mind, I unintentionally think mischievous things. Right now, in my house where I live alone, I am laughing out loud as I write these lines while sitting at my desk. Did our Tariq, when he set out on a journey, think “there is no turning back for me anyway” and take the opportunity to kidnap the woman he loved and go on the journey?

Don’t say it can’t be done; the Kurds’ actions are unpredictable…

If so, Tariq “burned the ships” in another sense…

To conclude the subject, let’s summarize it in its main points from beginning to end:

1 – Tariq ibn Ziyad, the conqueror of Andalusia, is neither Berber nor Arab. Tariq ibn Ziyad is a Kurd.

2 – Although Tariq ibn Ziyad was born in Algeria, who is described as an Algerian Berber in official history today and is believed by everyone in the world to be so, his family was originally from the city of Hamadan in Iran and he was the child of a family brought from Iran to Algeria as slaves.

3 – The claims that Tariq ibn Ziyad was Berber were first put forward in the 12th century. That is, 400 years after Tariq ibn Ziyad. The first person to do this was the geographer and cartographer Sharif al-Idrisi, who was also a Berber. Before him and before the 12th century, there is no record, not even a single written document, that says Tariq ibn Ziyad was Berber.

4 – The geographer and cartographer Sharif al-Idrisi, an Andalusian Berber, is not content with just making Tariq ibn Ziyad a Berber, he is trying to attribute Tariq to his own family, to make him his relative. He writes his name as “Tariq al-Idrisi” instead of “Tariq ibn Ziyad”.

5 – Berber historians who tried to make Tariq ibn Ziyad a Berber have also fallen victim to a bit of ignorance. All of the Berber tribes to which they attributed Tariq ibn Ziyad, who was born and lived in Algeria, were living in Libyan territory, not in Algeria, when Tariq was born and lived. This alone shows how the historians who tried to make Tariq a Berber made this claim with a false claim and spoke without any basis in knowledge.

6 – According to the earliest sources, Tariq ibn Ziyad was a Iranian born in Hamadan and was a freed slave of Musa ibn Nusayr himself or of the Said tribe. From the Almoravid Period onwards, Berber texts began to record that he belonged to the Nafza tribe.

7 – The claims that Tariq ibn Ziyad was Arab are a fabrication and historical distortion process that started even later than this date. After Berber historians wrote that he was Berber, Arab historians who “did not want to be left behind” also started writing that he was Arab.

8 – The reason why almost the entire world believes and thinks that Tariq ibn Ziyad was Berber is the result of the “fabricated history writing” that began in the 12th century, 400 years after Tariq ibn Ziyad. (Let me confess again: I was of this opinion until last year, and I believe the same.)

9 – In the early historical and official records in Spain, it is clearly written that Tariq ibn Ziyad was the child of a family from the city of Hamadan in Iran. This information is available in many reliable sources, especially the treasure trove called “Colección de Obras Arábigas de Historia y Geografía” (Collection of Arabic Historical and Geographical Works), which is the Spanish translation of the Arabic work called “Akhbar’un-Madjmoātun fi Fath’il-Andalūs”, which is the official historical records of the Islamic State of Andalusia and records the entire historical process from the time Tariq ibn Ziyad sailed into the Strait of Gibraltar in 711 to the end of the 10th century. The common opinion of the scientific world, historians and academics is that this work is generally far from legends and narrates historical events without exaggeration or distortion. In the comprehensive work called “Encyclopædia Universalis”, consists of 28 volumes, 30,000 articles and 32,000 pages and is based in France, which is published by the same organization that publishes the “Encyclopædia Britannica” based in Britain, in the article “Ṭāriq ibn Ziyād” written by French history professor and Arabic language expert Georges Bohas, there is information that Tariq ibn Ziyad came from a family of Iranian origin.

10 – The population of the city of Hamadan in the 7th century, that is, at the time of the “Islamic conquest”, was entirely Kurdish. This is a settlement founded and built as a city by the Medes, the ancestors of the Kurds. For this reason, even the phrase “med” in the name of the city of Hamadan refers to the Kurdish Medes nation, and the name of the city in its early periods, “Amedane”, literally means “place of the Medes” or “place where the Medes lived”. It is also clearly evident in official records in Iran and old Persian works that in the 7th century when the Islamic armies conquered Hamadan, the population of the city was entirely Kurdish. Therefore, the possibility that Tariq ibn Ziyad and his family were Kurdish is a hundred percent reality.

11 – The capture of Hamadan by the Arab Islamic armies in 645. Tariq ibn Ziyad’s birth date is 670. There is only and only 25 years between them. In other words, Tariq ibn Ziyad’s parents were enslaved by Muslim Arabs and brought from Hamadan to Algeria only 25 years later, Tariq was born in Algeria. Tariq ibn Ziyad’s parents, a Zoroastrian Kurdish couple whose names are unknown, were enslaved and taken from Hamadan to Algeria. This family later joined the staff of Musa ibn Nusayr, the Umayyad’s North African Governor, in Algeria, and became his slaves. Exactly 25 years after this tragic event, that is, only 25 years after his parents were taken from Hamadan to Algeria, Tariq was born.

12 – Tariq ibn Ziyad is not the child of a Muslim family. In fact, he himself was not a Muslim until a certain period of his life. Tariq ibn Ziyad, born in Algeria, was born and raised among Berbers, despite being a Kurd, he was raised as a Berber. His parents were not Muslims, they were Zoroastrians. He was not a Muslim at first, but lived as a Zoroastrian until a certain period of his life. He later became a Muslim and after becoming a Muslim, he was set free by Musa ibn Nusayr.

13 – The reason why Tariq bin Ziyad used the title “al-Layti” or “al-Laysi” is not because he was actually a member of this Berber tribe, but because he was a slave freed by this Berber tribe. In fact, Spanish historians think that Kurdish historian Khallikan used the expression “Tarik ibn Ziyad” here not in the sense of “Ziyad’s son Tariq” but in the sense of “Tariq who was saved from Ziyad”.

14 – The Berber sociologist Ibn Khaldun, who is considered the founder of the science of sociology, in his book “Tarikh’al-Berber” (History of Berbers), which is the 6th and 7th volumes of his magnificent work “Kitab’al-Iber wa Diwan’al-Mubtadā wa’l-Khabar fi Ayyam’il-Arab wa’l- Adjam wa’l-Berber waman Âsharahoum min Zawi’s-Soltan’il-Akbar”, later published as an independent work, says that there was a large Kurdish population living in Algeria and that they lost their ethnic identity and became “Berbers” over time. Ibn Khaldun even gives the names of some of the Kurdish tribes in this work.

15 – It is even debatable whether Tariq ibn Ziyad – as we are told – really set out to conquer Spain on Musa ibn Nusayr’s orders and assignment, or whether Tariq acted on his own, without listening to Musa or obeying his orders, by gathering a few warriors around him, even though Musa ibn Nusayr did not want such an operation and even tried to prevent Tariq. There are debates among different sources on this important issue, and many historians say that Tariq ibn Ziyad acted on his own. According to historians, Tariq ibn Ziyad took on tasks that were never given to him, and let alone conquering Spain upon Musa ibn Nusayr’s orders, did not even inform Musa ibn Nusayr while he was conquering Spain. When he learns about the conquest of Spain, Musa ibn Nusayr becomes very angry and starts to feel a grudge against Tariq ibn Ziyad. Musa ibn Nusayr is thinking of arresting Tariq ibn Ziyad and chaining him up, and even killing him. There is only one thing we need to understand from all this, and that is that only lies are told to us in both official and religious education by being called “History”. The Kurdish commander Tariq ibn Ziyad, who was a magnificent man, carried out this conquest independently with his own mind and the Berber warriors he gathered around him. He did not even inform Musa ibn Nusayr, in fact when Musa and the Umayyads heard about this they became very angry, they considered arresting Tariq ibn Ziyad and chaining him, and even killing him. In other words, the conquest of Spain in 711, the conquest of Andalusia, was not an achievement of the Umayyads, on the contrary, it was an achievement that was achieved despite the Umayyads.

16 – The first reference to Tariq ibn Ziyad in historical sources, in other words the oldest source mentioning Tariq, is the “Mozarabic Chronicle” written in Latin in 754. Although it was written only 43 years after the conquest of Spain, it interestingly mentions Tariq as “Taric Abuzara”.

17 – Some sources state that Tariq ibn Ziyad had a woman with him on all his expeditions and that when they crossed to Gibraltar by ship in 711 and conquered Spain, Tariq was accompanied by a woman named Ūmmū Hakim. However, the nature of their relationship remains unclear; whether this woman named Ūmmū Hakim is Tariq ibn Ziyad’s wife, sister or lover is unknown.

18 – I am an incredibly good researcher and writer, and this is an indisputable fact both religiously and scientifically. Despite the work I have done, there will still be some wicked corrupt people who will deny this. Also, according to what I have heard from people around, some people are talking against me, gossiping about me and badmouthing me in environments where I am not present. These are the things I hear. What can I say? I leave them to Marduk. Let the Anunnakis do with them as they see fit. Let the Mother Goddess Ishtar throw slippers at them…

Yes… This is the real identity, real personality and noble personality of Tariq ibn Ziyad, the real origin of his family.

Now let’s look at the real identity of the Andalusian Islamic Civilization.

In the religious history written by Arabs and Islamic historians who considered Arab worship as the “foundations of faith” and in the official history that repeats what they wrote, is the Andalusian Islamic Civilization that is presented to us as if it were an “Arab civilization”, is it really so? Or is it actually a “Berber civilization” built by Berbers, founded and maintained by Berbers?

Is Andalusia an Arab civilization or a Berber civilization?

Now let’s examine this interesting issue…

– will continue –

FOOTNOTES:

(270): İbrahim Sediyani, Adını Arayan Coğrafya, p. 37, Özedönüş Yayınları, Istanbul 2009 / İbrahim Sediyani, Die Verlorenen Länder Europas, p. 31, Koschi Verlag, Elbingerode 2022

(271): ibid / ibid

(272): Roger Collins, Arab Conquest of Spain (710 – 797), p. 97, Wiley & Blackwell Publishing, Oxford 1994

(273): Edgar Sommer, Kel Tamashek – Die Tuareg, p. 50 et seq., Cargo Verlag, Schwülper 2006

(274): Nuraddin al-Ālī, Tarikh’ul-Islam dar Arvupa-yi Gharbi, p. 79, Nashriyateh Danishgaheh Tehran, Tehran 1954

(275): Peri J. Bearman – Thierry Bianquis – Clifford Edmund Bosworth – Emericus Joannes van Donzel – Wolfhart Peter Heinrichs, Encyclopaedia of Islam, volume 10 (T – U), L. Molina, article “Ṭāriḳ b. Ziyād”, p. 242, Brill Publishing, Leiden 2000

(276): Jamil M. Abun-Nasr, A History of the Maghrib in the Islamic Period, p. 71, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge & New York & Melbourne 1987 / Hugh Kennedy, Muslim Spain and Portugal: A Political History of al-Andalus, p. 6, Routledge Publishing, London & New York 1996 / David C. Nicolle, The Great Islamic Conquests AD 632 – 750, p. 64, Osprey Publishing, Bloomsbury 2009 / L. Molina, ibid

(277): David C. Nicolle, ibid, p. 64 – 65

(278): Ibn Khaldun, Kitab’al-Iber wa Diwan’al-Mubtadā wa’l-Khabar fi Ayyam’il-Arab wa’l- Adjam wa’l-Berber waman Âsharahoum min Zawi’s-Soltan’il-Akbar, volume 1, Algiers 1851

(279): Ibn Izari, Al-Bayān’ol-Moghreb fi Ikhtisar-i Akhbar-i Mūlūk’il-Andalus wa’l-Maghreb, volume 1, p. 36 – 37, Algiers 1901

(280): Ivan Van Sertima, The Golden Age of the Moor, p. 54, Transaction Publishers, New Brunswick 1992

(281): Yves Modéran, Les Maures et l’Afrique Romaine (IVe – VIIe Siècle), École Française de Rome, Rome 2003

(282): Ahmad al-Maqqari, Nafh’ut-Teb min Ghushn’il-Andalus’ir-Ratib wa Zikru Waziriha Lisan’id-Din Ibn-il-Khatib, volume 1, p. 255, Cairo 1885

(283): Ibn Khallikan, Wafayat’ul-Āyān we Anbā-u Abnā’iz-Zaman Mimmā Shabata bi’n-Naql awi’s-Semā aw Ashbatah’ul-Āyān, Nashriyat’al- Najjar, p. 320, Cairo 1972

(284): Soadi Abd Muhammad, Tariq bin Ziyad, p. 19 – 23, Baghdad 1999

(285): Cambridge Encyclopedia of Islam, volume 2, p. 439

(286): Sharif al-Idrisi, Nūzhat’ul-Mūshtaq fi Ikhtiraq’il-Āfaq, volume 2, p. 539 – 540, Rome 1592

(287): Cambridge Encyclopedia of Islam, volume 2, p. 439 / Syaiful Hadi, Mengenal Panglima Perang Thariq bin Ziyad yang Rendah Hati, Infomu, 25 April 2022, https://infomu.co/mengenal-panglima-perang-thariq-bin-ziyad-yang-rendah-hati/

(288): Johann Heinrich Barth, Travels and Discoveries in North and Central Africa: Being a Journal of an Expedition Undertaken Under the Auspices of H. B. M.’s Government, in the Years 1849 – 1855, volume 1, p. 225 – 227, Longman, Brown, Green, Longmans & Roberts Publishing, London 1857

(289): Encyclopédie Berbère, volume 36, Abderrahmane Khelifa, article “Oulhassa (Tribu)”, p. 5975 – 5977, Éditeur Leuven, Paris 2013

(290): Rafael de la Morena, Tariq ibn Ziyad al-Layti: El Guerrero Olvidado, Web Islam, 28 December 2009, https://web.archive.org/web/20190131092850/https://www.webislam.com/articulos/37849-tariq_ibn_ziyad_allayti_el_guerrero_olvidado.html

(291): David C. Nicolle, The Great Islamic Conquests AD 632 – 750, p. 64 – 65, Osprey Publishing, Bloomsbury 2009

(292): Mahmūd Shākir, موسوعة اعلام وقادة الفتح الاسلامي, p. 108, Dar-u Usamat’il-Nashr wa’l-Tawziya, Amman, 2002

(293): Hisham Djait, Tasis al- Gharb’al- Islami, p. 199, Nashriyat-u Dar’al- Taliyah, Beirut 2004

(294): Josef de Abajo, Magrebí que Derrocó a un Rey y Conquistó España y Portugal, 6 April 2020, https://profesionaljdeabajo.wordpress.com/2016/08/08/todo-lo-que-hay-que-saber-de-la-esclerosis-multiple-durante-el-embarazo/el/

(295): Anwar G. Chejne, Historia de España Musulmana: Historia Serie Mayor, p. 11, Ediciones Cátedra, Madrid 1999 / Paulino Iradiel – Salustiano Moreta Velayos – Esteban Sarasa Sánchez, Historia Medieval de la Espan︢a Cristiana: Colección Historia Serie Mayor, p. 15, Ediciones Cátedra, Madrid 2010

(296): Wenceslao Segura Martínez, El Comienzo de la Conquista Musulmana de España, Al Qantir: Monografías y Documentos Sobre la Historia de Tarifa, issue 11, p. 94, 2011

(297): Emilio Gonzalez-Ferrin, Al-Andalus: The First Enlightenment, Critical Muslim, issue 6, p. 5, April 2013, https://www.academia.edu/3347289/Al-Andalus._The_First_Enlightenment / see also: Wikipedia (Spanish), article “Ajbar machmúa”, https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ajbar_machm%C3%BAa / Wikipedia (Catalonian), article “Akhbar Majmua”, https://ca.wikipedia.org/wiki/Akhbar_Majmua / Wikipedia (French), article “Akhbar Madjmu’a”, https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Akhbar_Madjmu%27a / Wikipedia (English), article “Akhbār majmū’a”, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Akhb%C4%81r_majm%C5%AB%CA%BFa / Vikipedi (Turkish), article “Ahbâr Mecmûa”, https://tr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ahb%C3%A2r_Mecm%C3%BBa

(298): Colección de Obras Arábigas de Historia y Geografía, volume 1: “Ajbar Machmúa”, translated by Emilio Lafuente Alcántara, Real Academia de la Historia, Imprenta y Estereotipia de M. Rivadeneyra, Madrid 1867

(299): S. M. Imamuddin, Sources of Muslim History of Spain, Journal of the Pakistan Historical Society, issue 1, p. 360, 1953

(300): Patricia E. Grieve, The Eve of Spain: Myths of Origins in the History of Christian, Muslim and Jewish Conflict, p. 249, Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore 2009

(301): Norman Roth, The Jews and the Muslim Conquest of Spain, Jewish Social Studies, issue 38, p. 145 – 158, 1976, https://www.academia.edu/45547207/Norman_Roth_The_Jews_and_the_Muslim_Conquest_of_Spain_Jewish_Social_Studies_vol_38_no_2_Spring_1976_145_158

(302): David James, A History of Early al-Andalus: The Akhbār Majmū’a – A Study of the Unique Arabic Manuscript in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris, with a Translation, Notes and Comments, Routledge Publishing, London & New York 2012

(303): Colección de Obras Arábigas de Historia y Geografía, volume 1: “Ajbar Machmúa”, translated by Emilio Lafuente Alcántara, p. 6 – 7, Real Academia de la Historia, Imprenta y Estereotipia de M. Rivadeneyra, Madrid 1867

(304): Ahmad ibn Muhammad al-Razi, Akhbar Mūlūk al-Andalus, Córdoba 955

(305): Ibn Qotiyya, Tarikh-i Iftitah’al-Andalus, Sevilla 977

(306): Ibn Hayyan, Al-Moqtabis fi Tarikh Ālimiya’l-Andalus, 10 volumes, Córdoba 1076

(307): Luis Molina Martínez, Un Relato de la Conquista de Al-Andalus, Al-Qantara: Revista de Estudios Árabes, issue 19, p. 39, 1998, https://digital.csic.es/bitstream/10261/13525/1/Molina_Un%20relato.pdf

(308): Encyclopædia Universalis, volume 8, Georges Bohas, article “Ṭāriq ibn Ziyād”, Société d’Édition Encyclopædia Universalis S. A., Paris 1966

(309): Colección de Obras Arábigas de Historia y Geografía, volume 1: “Ajbar Machmúa”, translated by Emilio Lafuente Alcántara, p. 6 – 7, Real Academia de la Historia, Imprenta y Estereotipia de M. Rivadeneyra, Madrid 1867

(310): Tres Textos Árabes Sobre Beréberes en el Occidente Islámico: Kitan al-Ansab, Kitab Mafajir al-Barbar, Kitab Sawahid al-Yîlla, Ibn Abd al-Halim, Abu Bakr ibn ‘Arabi, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Cientificas (CSIC), Madrid 1996

(311): Encyclopædia Universalis, volume 8, Georges Bohas, article “Ṭāriq ibn Ziyād”, Société d’Édition Encyclopædia Universalis S. A., Paris 1966

(312): Ibn Khallikan (trad. M. De Slane), Ibn Khallikan’s Biographical Dictionary [“Wafayāt al-A’yān wa-Anbā’abnā’ az-Zamān”], volume 3, p. 81, Oriental Translation, Paris 1843

(313): Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı İslam Ansikopedisi, volume 40, İsmail Hakkı Atçeken, article “Târık b. Ziyâd”, p. 24, Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı Yayınları, Ankara 2011

(314): Colección de Obras Arábigas de Historia y Geografía, volume 1: “Ajbar Machmúa”, translated by Emilio Lafuente Alcántara, p. 20, Real Academia de la Historia, Imprenta y Estereotipia de M. Rivadeneyra, Madrid 1867

(315): “The Battle of Qadisiyyah” and “Islamization of Iran” in all sources in the world

(316): “The Battle of Nahavand” and “Islamization of Hamedan” in all sources in the world

(317): Encyclopædia Iranica, volume 1, fascicle 9, E. Ehlers, article “Alvand Kūh”, p. 915 – 916, Mazda Publishing, Costa Mesa 2004

(318): Abdulhūseyn Nahchiri, جغرافیای تاریخی شهرها, p. 226, انتشارات مدرسه وابسته به دفتر انتشارات کمک آموزشی, Tehran 1370

(319): Ferdinand Hennerbichler, Die Herkunft der Kurden, Peter Lang Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2010, PDF of the German original: https://www.google.de/books/edition/Die_Herkunft_der_Kurden/-7jQvqeBks4C?hl=de&gbpv=1&dq=hurrian+kurds&pg=PA37&printsec=frontcover; Turkish PDF: https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/download/article-file/319040

(320): Gernot Windfuhr, Isoglosses: A Sketch on Persians and Parthians, Kurds and Medes, Acta Iranica, issue 5, p. 457 – 471, Leiden 1975

(321): Encyclopedia of the Developing World, volume 1, article “Kurds”, p. 922, Routledge Publishing, New York & Abingdon 2006

(322): Muhammad Raheem Saraf, شهرهای ایران, volume 3, p. 291, انتشارات فرهنگ و ارشاد اسلامی, Tehran 1368 / Roland Grubb Kent, Old Persian: Grammar – Texts – Lexicon, American Oriental Society Publishing, New Haven 1953